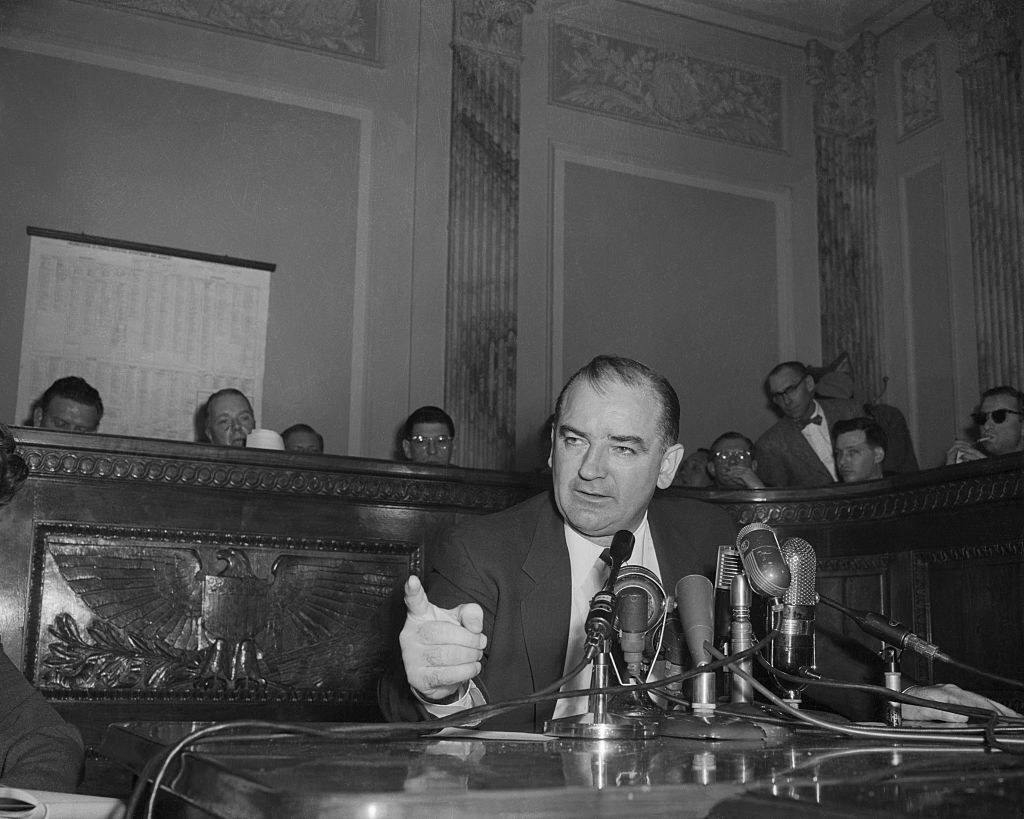

Donald Trump’s return to the White House has plunged Washington into upheaval and anxiety, bringing loyalty tests and other efforts to purge government employees. This climate of fear recalls the anticommunist paranoia of the 1950s and its crucial turning point exactly 75 years ago—when a famous speech, based on a lie, catapulted a little-known politician to prominence and added a new word to the American lexicon: McCarthyism.

[time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]

With that speech, Wisconsin Senator Joseph McCarthy seized the nation’s attention and would hold it for four years. Yet his words probably would have faded into obscurity if reporters hadn’t amplified and reinforced them — despite knowing they were false. The story of the speech offers a dire warning for the present, because it demonstrates how elevating the false claims of elected officials can distort American politics to catastrophic effect.

No one will ever know exactly what McCarthy said in Wheeling, W.Va., on Feb. 9, 1950. No recording of his speech survives, and the exact words he used became the subject of investigation and controversy. But news reports and McCarthy’s prepared text suggest that he painted a dark picture of the Cold War.

The senator asserted that five years after winning World War II, the U.S. was losing around the globe, locked in a struggle with communism that seemed destined to end in nuclear conflict. The blame for this terrifying scenario, McCarthy declared, rested with traitorous federal employees, who had sold their country out and had to be purged from its service. Near the end of his remarks, the senator made a more specific claim about the enemy within.

“I have here in my hand a list of 205…,” McCarthy (probably) said, “a list of names that were made known to the Secretary of State as being members of the Communist Party and are still working and shaping policy in the State Department….”

Although this sentence changed McCarthy’s life and the nation, it barely registered on the audience. As one witness recalled, McCarthy’s shocking claim “did not cause a ripple in the room.” The line came late in his speech, buried under paragraphs of alarming rhetoric that closely resembled what other Republicans were saying that weekend.

Ahead of the 1950 midterm elections, the GOP hoped to retake Congress with the slogan “Liberty Versus Socialism.” Many far more prominent Republicans than McCarthy spent that February weekend accusing Democrats of allowing communists to infiltrate the government. The prepared text of McCarthy’s speech drew on those same themes, including lines plagiarized from then-Congressman (and Senate candidate) Richard Nixon.

McCarthy’s office had hired two newspapermen from the Washington Times-Herald to assemble the speech text for him. In fact, when he arrived in Wheeling to headline a dinner honoring Abraham Lincoln’s birthday for a local Republican women’s club, McCarthy didn’t even know that he would give a speech on communism. McCarthy told his hosts that he could speak on either communism or housing policy, and they chose the former. Before revising the text himself, McCarthy gave a spare copy to a reporter who wrote an account of the speech in the Wheeling Intelligencer. Crucially, the reporter based his account on the speech text, not off of what McCarthy actually said.

This mattered because it was his article that ignited McCarthyism. In the eighth paragraph, the reporter repeated the claim from the speech text that McCarthy had “a list of 205” spies. McCarthy, however, later denied using that number, which was a distortion of something printed in the Congressional Record. Without the audio of his remarks, no one ever knew for sure if he made the claim or not.

Regardless, an Associated Press editor, who had not heard the speech, saw the Intelligencer report and issued an AP bulletin. Since most of McCarthy’s remarks followed standard Republican talking points, the AP bulletin zeroed in on the one part that seemed newsworthy. “Sen. McCarthy charged in an address here tonight that 205 Communist party members are ‘working and shaping the policy in the State Department,’” the bulletin began, giving this statement far more prominence than it had in the original text. The editor found the number questionable enough to check it with the Intelligencer, but he did not ask for corroborating evidence—such as proof that McCarthy’s list existed. After receiving confirmation that McCarthy had said “205,” the AP printed it—because, coming from a senator, the statement had news value, whether it was true or not.

The AP bulletin turned an unremarkable speech, given before a minor-league political group, into an alarming declaration about government—one that now demanded an official rebuttal. Relatively few newspapers published the initial AP dispatch. But when reporters caught up with McCarthy and told him the State Department had denied his claim, the senator’s insistence that he did have a list (but could not show it to them right now) made the story newsworthy once again.

Seeing that the claim brought him attention, McCarthy leaned into it in subsequent speeches, but he began using a smaller number of supposed spies: 57. He also belligerently demanded that the president and secretary of state name the alleged communists—which kept the story alive while shifting the responsibility for proving his claim onto Democratic officials.

Read More: Can He Do That? What Legal Experts Say About Trump’s Most Radical Moves

Reporters covering him that weekend knew McCarthy possessed few if any names. Some newspapers did point out his lack of evidence and refusal to identify any alleged communists on the record. But most journalists hesitated to openly question McCarthy’s claims, because objective reporting, as they understood it, meant passing his words along to the public—even though they possessed information suggesting the claim wasn’t accurate. At the time, norms dictated that journalists ought to report what elected officials said, and leave it to readers and listeners to parse out the truth.

The coverage started a snowball effect through which an unproven allegation, based on a supposed document reporters had not seen, turned McCarthy into a major figure—one who gained power from his newfound fame. The senator proved enough of an opportunist to seize the moment, and he continued to draw attention for years to come. Yet, in a real way, his rise was a media creation. The ramifications would prove massive for the hundreds of Americans targeted by McCarthy’s investigations or called to testify before his Senate subcommittee. And as McCarthy’s activities stoked fears of anticommunist subversion, thousands of additional Americans, by some estimates, lost their jobs, their freedom to speak or travel freely, and even their lives for being suspected of left-wing beliefs or associations. McCarthy’s reign of terror only ended when he went after the U.S. Army, which repelled some of his fellow Republicans. They joined with enough Democrats to censure him.

All of the human tragedy spurred by McCarthy sprang from the definition of objectivity that guided political journalism at the time. Four months after McCarthy’s speech, journalist Douglass Cater summarized the problem: American political media was “a system of loudspeakers that transmits and amplifies the words uttered in the public arena.” This practice empowered a growing number of people who knew “how to capture that instrument and scream all they want into it.”

This basic dynamic remains true 75 years later—arguably it has only gotten worse. Some of the most influential figures in American politics today won their power and prominence the same way McCarthy did—not from passing legislation, serving on important committees, helping their constituents, or skillfully mastering policy areas—but because of their willingness to say outrageous things that capture the attention of the news media.

Beyond the damage to individuals, the consequences of platforming such voices, without challenging their claims, can be severe, far-reaching, and impossible to predict. In the 1950s, attacks from McCarthy and other Republicans led to a purge of State Department diplomats, including East Asia experts whose knowledge might have helped the U.S. avoid or mitigate its disastrous involvement in the Vietnam War.

Now the Trump Administration has launched an even broader purge of the government, while pledging to eliminate “DEI” from the federal bureaucracy. What began with the firing of inspectors general and the removal of officials in global public health and aviation safety has escalated into an attempt to downsize the entire federal workforce through buyouts. This aggressive campaign poses many threats, both to government functionality and national security.

The media needs to expose the reality of this attack on the civil service: it’s a costly new form of McCarthyism, one that is full of falsehoods and is of dubious legality. That’s especially true because the U.S. is far more polarized than in the 1950s, making it less likely that elected officials will denounce or censure a member of their own party.

McCarthy’s rise and the damage he did hammers home that, now more than ever, Americans need journalism that actively separates truth from falsehood. Without such reporting, we will remain at the mercy of misinformation that, like McCarthy’s lies, can hold the power to reshape our political reality for another three-quarters of a century.

A. Brad Schwartz is a doctoral candidate in American history at Princeton University and the author of Broadcast Hysteria: Orson Welles’s War of the Worlds and the Art of Fake News. He is writing a biography of Edward R. Murrow.

Made by History takes readers beyond the headlines with articles written and edited by professional historians. Learn more about Made by History at TIME here. Opinions expressed do not necessarily reflect the views of TIME editors.