Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s nomination to lead the Department of Health and Human Services has the potential to drastically reshape the public health landscape. Kennedy, an environmental lawyer who ran as an independent in the 2024 presidential election before throwing his support behind Donald Trump, has expressed discredited claims that childhood vaccines are linked to autism and has advocated for a holistic approach to health. If he were to oversee government agencies like the CDC, NIH, and FDA, scientists fear that he could encourage states to weaken vaccination requirements.

[time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]

The controversial nomination—and the relative popularity of Kennedy’s Make America Healthy Again (MAHA) movement—speak to a larger mistrust of expert knowledge. Yet they also fall within a longer contestation over state power, health, nature, and the body. From its inception, the anti-vaccine movement has been intertwined with a range of political, moral, and spiritual ideas around the rights of the individual versus the community, the limits of governmental power over bodily autonomy and faith in medical expertise, and institutional knowledge.

Read More: Why People Believe Trump and RFK Jr.’s Dangerous and Debunked Claims about Vaccines and Autism

In the early-to-mid 19th century, most Americans welcomed vaccines against smallpox. Cowpox-based smallpox vaccines, which drastically improved upon riskier live smallpox inoculations, were first trialed in the United States in 1800 and quickly embraced by prominent figures such as Thomas Jefferson and James Madison. Under Madison, “An Act to Encourage Vaccination” was passed in 1813, which provided for distribution of vaccines by mail. In newspaper coverage, vaccination was frequently represented as a measure of progress and enlightenment.

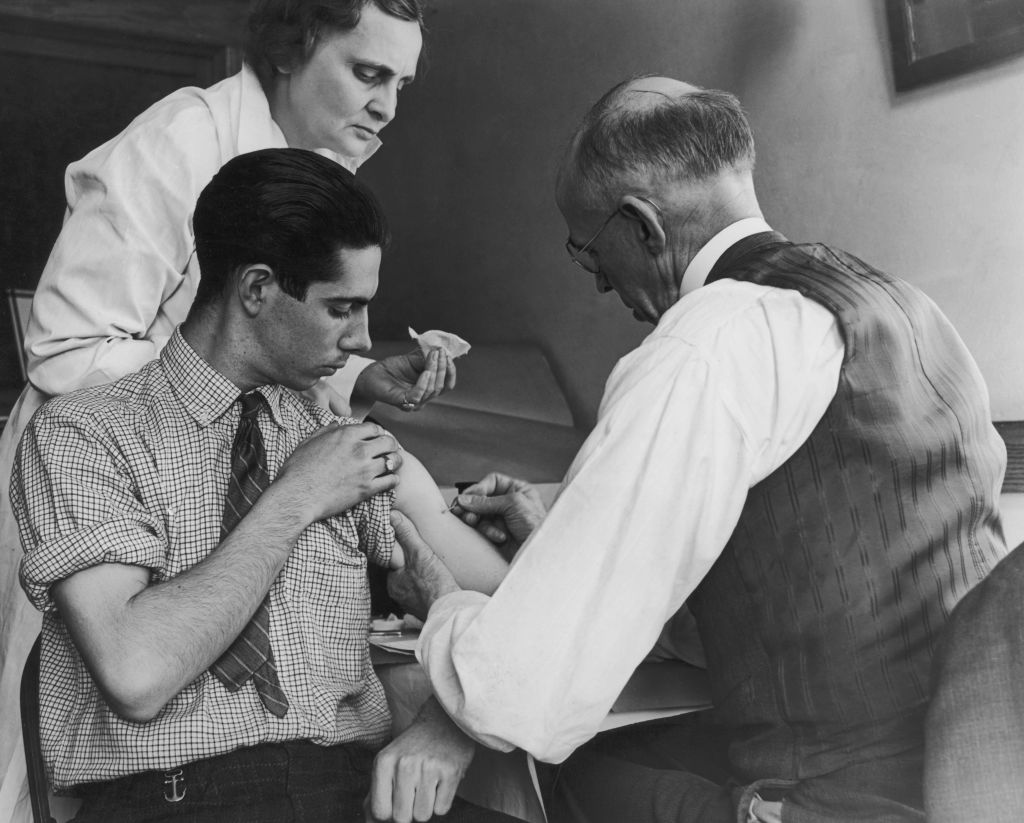

The efficacy of vaccines prompted some states to take a heavier hand in trying to eradicate the disease. In 1855, Massachusetts became the first state to mandate smallpox vaccination for children enrolled in public schools. By the early 1900s, several states had adopted similar policies. Given the devastatingly high mortality rates associated with smallpox, these laws were justified as measures to protect the general welfare.

While smallpox vaccines had previously garnered pockets of local resistance as alternative medical practices became more popular, the implementation of mandates intensified the opposition by giving it a new focus. Inspired by British activism over the same issue, the Anti-Vaccination Society of America formed in 1879. The organization adopted a twofold strategy, including advocacy for alternative remedies, such as homeopathy and naturopathy, and legal challenges to mandates.

A particularly far-reaching law escalated the matter to the Supreme Court. In 1902, the city of Cambridge, Mass., made the smallpox vaccine obligatory for all municipal residents; if they refused, they would incur a $5 penalty. In response, Henning Jacobson, a minister who had previously immigrated from Sweden, legally challenged his fine by arguing it was unconstitutional. Jacobson claimed that “compulsion to introduce disease into a healthy system is a violation of liberty.”

Like the anti-vaccine movement in Great Britain, this strategy of resistance to the smallpox vaccine relied heavily on liberal fears over government intrusion into “private” matters such as personal health and childrearing. Alfred Milnes, a prominent British anti-vaccination advocate, maintained that even if he could not convince his audience that vaccinations were ineffective, he hoped to win them over on the merits of personal liberty. Similarly, Jacobson argued that Cambridge’s vaccine mandate threatened his rights as an individual.

The Supreme Court disagreed. In a 7-2 decision, the Court upheld the law as a matter of self-defense, reasoning that restrictions on individuals can be justified for the public health of the community. Smallpox, a disease with a 30% fatality rate, and which often left survivors with severe scarring, qualified as such an emergency.

And yet, such anti-vaccine justifications had found fertile ground in turn-of-the-century America among proponents of alternative healing who mistrusted mainstream medical expertise. Immanuel Pfeiffer, an opponent to Boston’s vaccination laws, wrote in Our Home Rights, a Massachusetts-based periodical, that the right to resist tyranny was “inalienable” and mounted a passionate defense of individual bodily autonomy. In his view, protesting such an injustice was not just a right, but a duty. While vaccinating oneself and one’s family was an individual choice, he granted, forcing others to undergo a vaccination was not. He argued that if vaccines were truly effective, then the unvaccinated would be dangerous only to themselves. (In fact, unvaccinated people can be dangerous to those who are immunocompromised or unable to receive the vaccine.)

Others in the anti-vaccine movement focused on the purported inefficacy of the smallpox vaccine. In one of his milder invectives, Pfeiffer compared vaccination to “charms” or “witchcraft,” arguing instead that poor hygiene and sanitation caused smallpox—as well as diphtheria and cholera—to fester. This critique linked to broader Progressive-era politics that sought to improve sanitation measures.

At the same time, anti-vaccination movements represented a reaction against Progressive successes in increasing government control over public health. By the turn of the century, there was strong support for greater standardization of medical education and licensing; the American Medical Association solidified its role as the representative of an increasingly professionalized medical orthodoxy. Vaccine resistance, in turn, was particularly pronounced among alternative health practitioners like Reuben Swinburne Clymer, who lamented how despotic doctors overrode the objections of ordinary citizens. Other articles in Our Home Rights protested how increased regulation over medicine had led to the prosecution of those practicing medicine without a license.

Moreover, Clymer suggested that vaccines were not just ineffective, but dangerous. He argued (contrary to evidence) in a 1901 issue of Our Home Rights that vaccinations were hazardous to human vitality and could cause death, particularly among the already vulnerable.

Read More: What Donald Trump’s Win Could Mean for Vaccines

Instead, Pfeiffer and Clymer championed self-healing. Both were involved in the New Thought Movement, a 19th-century spiritual movement that emphasized metaphysics and portrayed disease as an error of thought. Consequently, a holistic and healthy lifestyle in harmony with God would cure all ills. Healing must be either mental or “natural.” Our Home Rights had a Botanic Medicine Department that promoted herbal and botanical remedies, juxtaposing cures that came from “nature” against an alienated medical profession. Premised on a view of the human body as a holistic microcosm of a pristine natural world, healing resulted from internal development instead of external injection.

As mainstream medical opinion crystallized in favor of vaccination, the combination of liberal political values, holistic ideas about the body, and alternative health entrepreneurship shaped vaccine resistance after the Jacobson ruling. While the movement failed to discredit vaccination to the government or the scientific establishment, it achieved more modest gains, as many states began to allow for conscientious objection, limiting the compulsory element of the mandates.

Today, the political and legal system could move beyond merely accommodating conscientious objectors; it could introduce barriers to vaccine development or influence state policy to encourage vaccine refusal. This is not isolated to Kennedy. Indeed, reticence towards Kennedy’s nomination from some Senate Democrats and even a number of Republicans skeptical of his eclectic political views may render it unlikely to succeed. The novel factor is rather how anti-vaccine ideas have become relatively normalized through much of the Republican party leadership and will likely shape policy to an unprecedented extent.

The turn-of-the-century resistance to the smallpox vaccine shows us that anti-vaccine beliefs do not arise in isolation. Taking seriously and engaging in dialogue over these root causes, rather than simply debunking anti-vaccine beliefs by themselves, is increasingly necessary.

Helen L. Murphey is a Postdoctoral Scholar at the Mershon Center for International Security Studies at the Ohio State University; her research interests include social movements, populist political culture, and disinformation.

Made by History takes readers beyond the headlines with articles written and edited by professional historians. Learn more about Made by History at TIME here. Opinions expressed do not necessarily reflect the views of TIME editors.